rezized2.jpg)

The Echenbergs of Ostropol and Sherbrooke:

A Tale of Two Shtetls

Myron J Echenberg and Ruth Echenberg Tannenbaum

Extracted and revised for Sherbrooke and Ostropol Kehilalink sites by Dean Echenberg

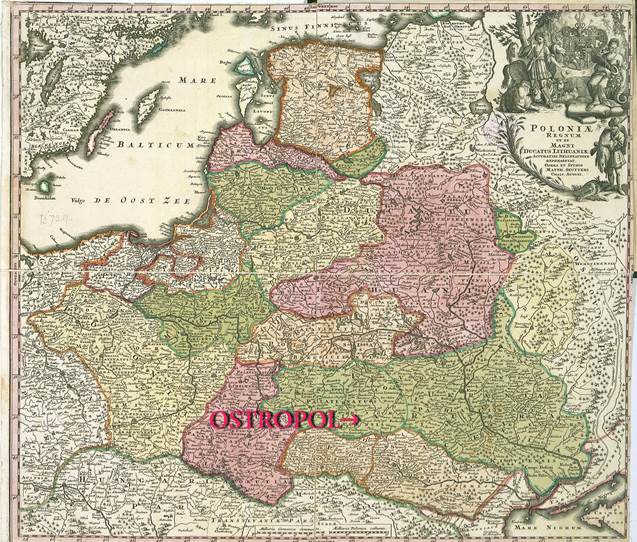

Early Map of Polish Empire with Ostropol clearly marked in the original.

I. Early Jewish Life in the Ukraine

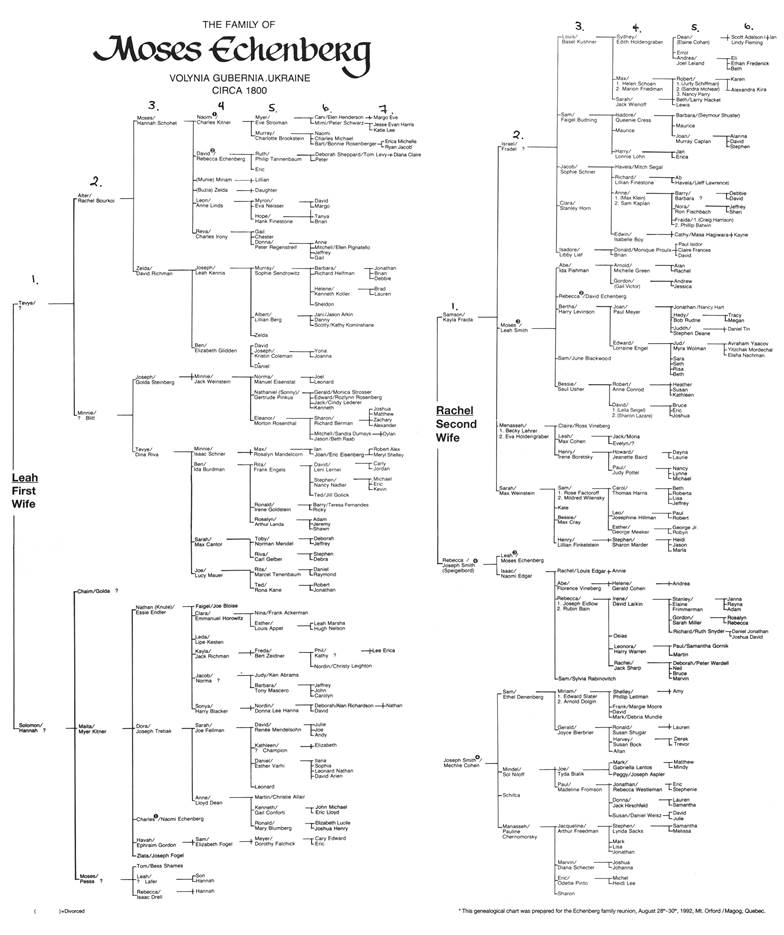

Our family's beginnings derive from a single ancestor, Moses, of whom only the barest facts have been transmitted orally. We know only that he was born at the beginning of the nineteenth century in the Jewish shtetl town of Ostropol, in the province of Volynia, located in the heart of the Ukraine, Eastern Europe's bread basket. Who his parents were, and why our family history begins with Moses are questions we simply cannot answer. We do know that our founder Moses had two families, an older branch descended from his first wife, and a junior branch from his second marriage upon the death of his first spouse. However obscure the personal circumstances of Moses were, it is possible to place him in historical context. While Jews had been living in Volynia for at least five centuries at the time of Mose's birth, all the peoples of the region, Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews alike, were in the midst of a major political transformation. In 1793 the second partition of Poland had just occurred, bringing most of the Ukraine, and all of the province of Volynia under formal Russian rule for the first time. Further west in France, a Revolution which would change the map of Europe and its ideology forever, was in full swing.

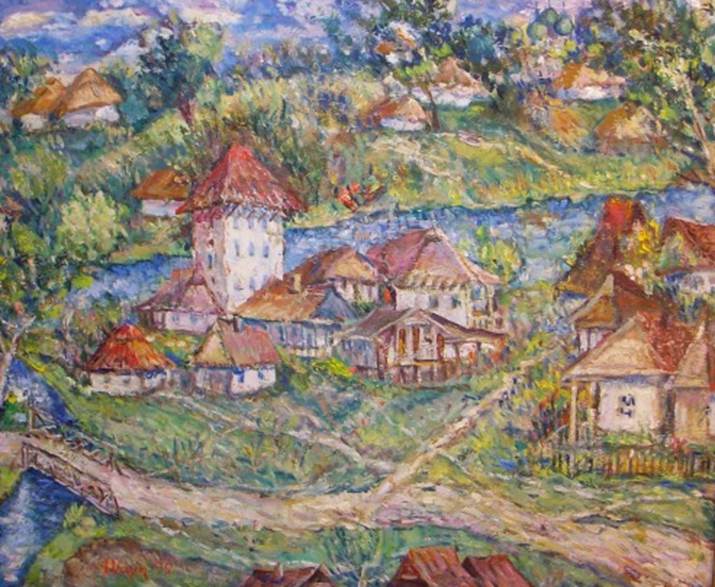

Ostropol by Isak Vaynshelboym

Our founder may very well have been the first Echenberg even if he was assuredly not the first Jew of Ostropol. While Jewish life in the Ukraine can be traced back to antiquity, it is more likely that our ancestors first settled there as part of a large-scale eastern migration of Ashkenazi Jews from German speaking to Slavic lands beginning in the late twelfth century. One reason why our family history begins so relatively late may be that, save for great rabbinic scholars, Eastern European Jews did not place much emphasis on genealogy and individual family history as opposed to study of the Talmud and the collective history of the Jewish people. A second reason may be linked to nomenclature. While some Jews of the East had adopted formal patronymics or family names, most Jews, and indeed, most Gentiles in Eastern Europe used the older, biblical practice of using their father's name to identify themselves, for example, as Moshe Ben Avrum, or Rachel bas Avrum, which were rendered in Polish or Russian as Moshe Abramovitch and Rachel Abramovichova. It may be that one of the first consequences of the transfer in Ukrainian sovereignty from Poland to Russia that marked the period of our ancestor's birth was that Jews would now be required to adopt formal patronymics. While some may have enshrined their family names as Abramovitch, others chose place names, such as Nemirov, or occupational names such as Schechter (butcher), Schuster (shoemaker). Our own name seems to be the Yiddish, "Hech en barg", or "high on the hill", perhaps denoting the family residence on raised land. The topography of the Ukraine is such that "Mountain", or "Lamontagne" would not be appropriate anglicanization or francization of our name, but "Hill" would be closer to the original Yiddish. It should be noted that two sisters of Leon and Reva Echenberg, Munya and Buzya, who stayed on in Russia and became secular participants in the emancipation of Jewish women in early years of the Russian Revolution russified their names to Goryna, the feminine for Goryn, or Goren, which is Russian for hill.

The Echenberg family made its living as egg merchants. They were part of a very long standing economic activity, the exporting of agricultural products from Eastern to Central and Western Europe. They purchased eggs in volume from local Ukrainian peasants at the Ostropol market, and also had Jewish peddlers collect eggs from the countryside directly; they then exported this product west to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It is probable that our ancestors were involved in this particular commerce for generations. In the late nineteenth century, several branches of the family were employed in various facets of the egg business, supervising purchase, sorting and packaging, and long-distance exporting of this commodity.

" The latest statistics with regard to the importation of Russian farm produce into England fully bears out the review that English agriculture would do well to wake up and "look alive". It has long been know that Russia supplies England with nearly half as much wheat, oats and barley as are grown in the whole of England. But it could scarcely have been believed that Russia, amoung other items, supplies England with 200,000 eggs a year. What a disastrous testimony."

From the "International Herald Tribune " Paris: May 15, 1895

Several Echenberg families have preserved a memory of this particular business, which was under the overall direction of Alter Echenberg and his wife Rachel. Rachel ran the business in Ostropol, pouring over her accounts from morning to night with consummate attention to every last detail, her glasses perched at the tip of her nose. Alter lived near the Austrian border at Volochisk for most of the year, supervising the exporting of eggs to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. On occasion he would himself cross the border into Austria, and, more rarely, travel to Vienna and other major cities of Central Europe. Leon and Reva recount how their grandfather Alter would return home twice a year for Yom Tov with special little gifts, such as oranges, dates, and even a perambulator with metal wheels, items entirely new to the industrially backward Ukraine. On the other hand, Alter, who was an extremely traditional and pious Jew in dress and deportment, was not a vehicle for modernization of Echenberg family life. Grandmother Rachel, or Baba Rachel as she is affectionately remembered, was clearly the driving force behind the family egg business, while Alter did the travelling, and, perhaps, the studying of Talmud and dedication to prayer that filled much of the observant Jew's daily life. Baba Rachel was reputed to be an extremely shrewd and tight-fisted lady whose habit it was to hoard children's new pencils and other small gifts against emergencies. Still, such excessive frugality was born of necessity, given the sometimes precarious existence of these fragile communities.

Alter Echenberg and his family in Ostropol, c 1895

Alter and Rachel Echenberg headed a family of status and authority in the shtetl. Their relative prosperity, Alter's piety, and Rachel's intelligence combined to make them and the Echenbergs generally, balabatim, leaders of Jewish life and especially of the obligation or mitzvot of charity. For example, a balabatische family was expected to prepare twice as much food as was needed for Sabbath, for distribution to the poor. We do not know for certain whether the pioneer of our family, Moses, son of Samson and Clara Echenberg, actually worked for a time in the egg business before he left for the New World at the age of twenty-three in 1886. He was of the junior branch of the Echenbergs, his father Samson having been a half-brother of Tevye, Alter's father, and therefore a "half-first cousin" of Alter. Perhaps, given the growing economic pressures on Jews in late nineteenth century Ukraine, it may have been that Mose's prospects in the egg business were not great, and that it was precisely this economic motivation which prompted him to set out like millions of other immigrants in search of better opportunities in the New World. While we have no evidence for this construction, we can more confidently state that Moses shared with Alter Echenberg's senior branch the values of a balaboss. As we shall see, he and his younger brother Menassa were to become the leading Echenberg balabatim of Sherbrooke, our New World shtetl.

By the later part of the nineteenth century, economic and social changes were reflected in the family activities. While the older generation remained as· agricultural exporters, Alter's son Moses, a bearded but much more secular man, earned his living as a minor government official, the magistrate, or staritsa, for Jewish residents of Ostropol, who needed passports to travel within the Tsar's lands and documents to indicate their military status with regard to universal conscription. A cousin, Charles or Shame Kitner, was a watchmaker in Ostropol. A family photo taken in Ostropol around 1910 depicts Shame's small shop in the background. Shame remained a watchmaker and retail jeweler in the New World, opening retail stores in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, first in Megantic, and later in Drummondville. His sons Myer and Murray continued and greatly expanded Kitner Jewellers, opening branches in several Quebec towns and cities, including Montreal. Though semi-retired, Myer in Montreal, and Murray in Florida, both continue to be active in the jewellery business. One of Shama's grandsons, Bart, has specialized in that most timeless of jewels, gold, representing at least the third generation in this trade. Alas, as far as we can tell, however, no Echenbergs are still in the egg business.

Murray Kitner and family standing in front of

his jewellery store in Ostropol

Whatever the small economic successes of Echenbergs in Ostropol, there was not enough opportunity to provide a livelihood for an expanding family. Even in normal times, out-migration would have been a logical expectation, and Jews of nineteenth century Russian Ukraine did not live in normal times. Why Echenbergs migrated across thousands of miles of land and water to the Eastern Townships of Quebec is not so obvious, however, even though, in this as in other aspects, our family's history follows very closely the patterns for Ukrainian Jews as a whole. To put our family emigration in context, a brief examination of the main lines of Jewish History in Eastern Europe is in order.

Jewish beginnings in the Ukraine

15th Century map of Ukraine. Ostropol in original at end of red arrow.

A Jewish presence in what became Russia dates back to Antiquity. As early as the eleventh century when the Princes of Kiev were accepting Greek Orthodoxy, Jews were residents of that city. Kiev was in trading communication, and sometimes at war with the Crimea, an area of concentrated Jewish trade and culture from ancient times, settled by Jews who migrated there directly from the Middle East. In addition, the Khazar rulers of a state in the Crimea converted to Judaism. But the numbers of Jews in Eastern Europe grew significantly beginning with the First Crusade (1096) and especially after the Second (1147) and Third (1189-1192), when conditions in Germany became difficult for Jews.

Ostropol(in box lower right)in relationship to 20th Century Poland

Jewish immigrants poured into Poland, first in border provinces of Cracow, Posen, Kalisz, and Silesia. By numbers and superior training in Judaism, these immigrants imposed their German dialect on Polish Jewry, gradually producing the Yiddish language. Jews rose to positions of considerable importance under the protection of the Polish princes, as administrators, farmers, artisans, and generally as a middle stratum between nobles and peasants. Banking became an especially important activity as the medieval doctrine held that Jews were the property of the Crown, empowered to be moneyed men so as to supply the treasury with funds. Greatest gains were made under Casimir the Great, 1333-1370, during which time more German Jews flocked to his lands. Jews were permitted to rent or mortgage estates of the nobility, and to have unrestricted domicile in any of the cities or villages.

It is possible that the Jewish shtetl in Ostropol dates back to Casimir's time in the mid fourteenth century. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, however, relations had deteriorated, highlighted by the old calumny of Jewish ritual murder of Christian children, this time brought forward in Cracow during Easter of 1407. It led to one of the first vicious pogroms, with the Jewish quarter attacked, many killed, children baptized, property looted, and dwellings set on fire. The Polish king Casimir IV, who ruled in the mid fifteenth century, wished to protect Jews and secure a Polish foothold on the Baltic seaboard against the Teutonic Knights. But a military defeat cost him this goal and forced him to make concessions to the Polish nobility that marked the beginnings of curtailment of royal powers in Poland relative to the nobility. Jews suffered as a result, without a strong monarchy to protect them. A weakened royal authority could not prevent local magistrates from restricting Jews from urban life and occupations. Guilds excluded Jewish artisans and ghettos became strictly enforced in such Polish cities as Posen. Warsaw permitted no permanent Jewish residents while limiting Jewish merchants to no more than a two or three day stay. These constraints pushed Jews further east and south into the smaller towns and rural villages of such Ukrainian provinces as Podolia, Volynia, and Kiev, where Jews took on the vulnerable position as middle men between Polish nobles and Ukrainian peasant serfs.

Compared to harsher conditions and expulsion orders in Western and Central Europe, however, the East continued to be a region of relative security for Jews. Migration and population growth saw the numbers of Jews under Polish rule rise from 50,000 at the beginning of the sixteenth century to half a million by the mid-seventeenth. This period established the high water mark of Polish Jewry, intellectually and materially. Jews were not restricted to money-lending or petty trade; they were active producers and manufacturers in various industries. Some leased and administered Crown domains and estates of the gentry. Jewish capitalists worked salt-mines or dealt in timber and Jewish merchants exported the agrarian products of the country beyond the border. The poorer classes were traders, craftsmen, or tillers of the soil. Our family's egg business, therefore, reflected a typical middle stratum economic activity of Jews in the eastern lands.

Modern Jewish historians are revising earlier impressions of Jewish History in the Diaspora. They are contesting what one scholar has called "lachrymose history", the view that Jews in the Diaspora have experienced nothing but persecution and suffering for over two thousand years. While not denying the irrefutable evidence of brutal discrimination and persecution at various dark moments, the new school points out that .Jews have also experienced long periods of stability, allowing for rich spiritual and cultural expression, and an economic condition that was superior to that of most of the other peoples among whom they lived.

An Evening in Ostropol, Matthew Mosenkis

The Polish Ukraine from the reign of Casimir the Great in the mid fourteenth century to the "time of troubles" ushered in by the Cossack rebellion under Bogdan Chmielnicki some two hundred years later, in 1648, was one such region of relative Jewish well being. As food exporters living in one of Europe's most fertile regions, our ancestors lived comfortably. Jewish spiritual life flourished under Polish rule, with many centres of learning stretching from Cracow in Western Poland to Zhitomir near Kiev.

Ostropol was a typical shtetl in the centre of Volynia, itself the geographic centre of the Polish Ukraine. Two of its most famous sons, Samson or Shimson ben Pesah Ostropoler, and Hershele Ostropoler, have given the town renown in .Jewish philosophy and popular culture respectively. No details of Shimshon's life are known save through his own writings. He was regarded throughout Poland as the greatest Kabbalist in the country, a powerful mystic who concerned himself with numerological mysticism and demonology. He served as preacher in Polonnye, not far from Ostropol, where he died a martyr's death in 1648, a victim of the Chmielnicki massacres.

Ostropol is also associated in Jewish folklore with the late eighteenth century humorist known as Hershele Ostropoler. He was born in Balta in the neighboring province of Podolia, and lived most of his life in Medzibozh, where he died. But his name derived from Ostropol because he served there for a time as a shohet. Many stories associated with Hershel have been recorded by such giants of .Jewish literature as Shalom Alecheim and Isaac Bashevis Singer. Some may not be authentic but there is no doubt Hershel actually existed and admirably reflected the sort of wry humour often associated with persecuted minorities. The following story, recounted by Leon Echenberg, who heard the story from his father Moses, nicely demonstrates the ability of shtetl Jews to fight discrimination with humour.

One day Hershel was visiting a village some distance from Ostropol when the local Polish lord, accompanied by his entourage, rode into the main square. All the locals took off their hats and bowed in subservience to this powerful figure, all, that is, except Hershel. When the lord noticed that Hershel was not following the village practice he ordered his coachman to stop in front of this cheeky Jew. " Where are you from?'', the lord angrily snapped, whereupon Hershel replied, "from Ostropol". "What about the hat?" asked the lord. And Hershel answered, "The hat too is from Ostropol,"

The Chmielnicki uprising of the mid seventeenth century marked a period of considerable unrest in Europe generally (English civil wars, inflation and decline in Spain, religious wars in Germany). In 1648 the Cossack leader Bogdan Chmielnicki, led a revolt against the Polish nobility. After defeating the Polish army, his followers joined with local Polish and Ukrainian peasants in attacking the Jews. Spasmodic violence continued for eight years, with an estimated 100,000 Jews killed; many others were tortured or ill-treated while others fled to Holland, Germany, Bohemia and the Balkans. No anti-Jewish massacres were recorded for Ostropol but the town could not escape the anti-Semitic hatred boiling throughout the region, Shimson Ostropoler himself was martyred at the head of his community in Polonnye, which was less than one day's travel from Ostropol. Persecutions and pogroms continued during the period of Muscovite occupation of Volynia, Podolia, and Kiev until the Polish army was able to put down the rebellion and drive off the Muscovite invader in 1667.

One consequence of the holocaust was the rise of messianism, specifically the movement of the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi. Although he was a Sephardic Jew born in Smyrna (Izmir) in the Ottoman Empire, he acquired a large following among the spiritually and economically devastated Ashkenazi communities of Eastern Europe. An even more important new movement was that of Hasidism or Pietism which arose in the province of Podolia, immediately west of Volynia, where Jewish misery was at its worst. Among its other features, this new mystical movement, while not itself sectarian, aroused doctrinal splits in an already hard pressed Jewish community. Under these circumstances the centres of Jewish culture and learning moved north to Poland and Lithuania, leaving the Jewish Ukraine to become an impoverished commercial and intellectual backwater.

II. Ostropol under Russian Rule

While Jewish life was declining a similar fate struck the Polish state at the expense of its more powerful neighbors, Sweden, Austria, Prussia, and especially Russia. The first partition of Poland in 1772 enabled Russia to begin a western expansion by annexing a few border territories. In 1793, the second partition of Poland brought most of the Ukraine under Russian rule, pushing the western border of Russia to a line just west of Pinsk, and bringing all of Volynia, and Ostropol with it, under the sovereignty of the Russian Tsars. Our family founder, Moses, was the first of his line, therefore, to come under Russian rule. He was not alone. This westward expansion of Tsarist Russia suddenly brought over 1,200,000 Jews under Russian sovereignty, a situation the Russians labeled a "Jewish Problem", as it had been their practice to expel Jews from Russia whenever their number grew threatening. Expulsion of such a large number was out of the question, but the Russian authorities now tried to contain the Jews within the newly annexed territories. They created the "Pale of Jewish Settlement", beyond which Jews were not allowed to reside permanently.

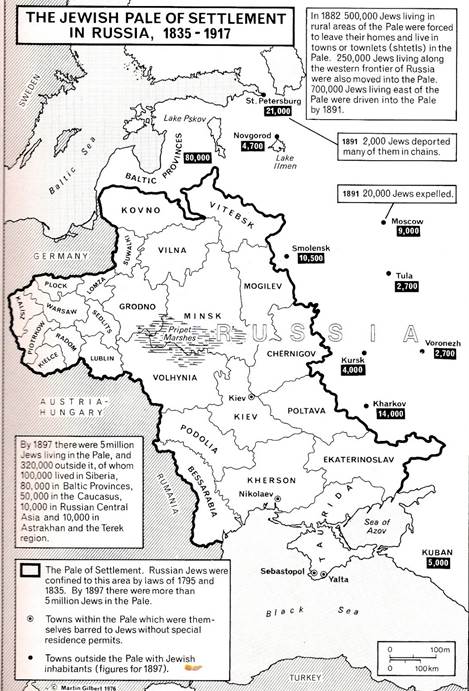

The Pale of Settlement. Ostropol is situated at the junction of Kiev, Volhynia and Podolia provinces.

These and other such constraints helped persuade over two million Jews, including our own ancestor Moses, to set out for the New World. Pressure for Jewish migration from Russia is part of a complex pattern of world history which saw millions of migrants leave the Old World for the New. Broadly speaking, causes of this worldwide phenomenon can be traced to three factors; 1)the push of population growth; 2) the push of old and new forms of persecution; and 3) the pull of the New World as the land of opportunity.

All over Europe the nineteenth century witnessed unprecedented population growth. Historical demographers attribute this phenomenon to falling death rates, caused mainly by the massive rise in food production and especially distribution, and, later in the century, by the beginnings of immunization practices and other first steps in what came to be called public health measures. As more people survived infancy and childhood, however, the risk of impoverishment faced millions of families as they scrambled to find a livelihood for their larger numbers.

Although census data are somewhat imprecise, the following figures indicate the dimensions of the population explosion in nineteenth century Russia:

Year |

Jews in the Pale |

Jews in Poland |

Total Russian Population |

1820 |

1,200,000 |

400,000 |

46,000,000 |

1851 |

l,000,000 |

600,000 |

61, 000,000 |

1880 |

3, 000,000 |

1, 000,000 |

86, 000,000 |

1910 |

4, 000,000 |

1, 400,000 |

132, 000,000 |

Jewish Population in Poland and the Pale 18th century.

It should be noted that the Jewish population was rising at an even faster rate than the general population. In the six decades from 1820 to 1880 for example, Jewish population increase was 150% versus 87% for the general population. In the next period, despite massive emigration, Jews under Russian rule increased by 29%, just slightly below the general population increase of 34%.

A population explosion of these dimensions need not have by itself created increased misery for the various subject populations of Russia. But the severe contradictions of a corrupt and inefficient state bureaucracy combined with a backward technology and a narrow ideology to produce one disaster after another for the mass of the population, Jew and non-Jew alike. In Tsarist Russia, an always conservative monarchy turned reactionary under these pressures, virtually guaranteeing a bloody revolution from below in 1917.

As inept as the Russian state was in dealing with its problems in general terms, its response to what it labeled its "Jewish Problem" was both contradictory and mean-spirited. Jews were not permitted freedom of movement beyond the Pale even as the strains on the resources of the region grew enormous. Grudging concessions were made, enabling a small minority of Jews, for example, bankers with substantial financial resources, to escape to larger towns. Few such Jews could be found in the Ukraine, unlike the somewhat more prosperous regions of Poland and the Baltic seaboard. Other exceptions were made for children with musical, artistic or intellectual gifts. They and their immediate families were permitted to settle in larger centres. Needless to say, this privilege greatly stimulated Jewish artistic and intellectual activity over three generations and led to the prominence of Jews in the cultural and scientific life of Russia. Many others lived outside the Pale (hence the expression "beyond the Pale") illegally, and if discovered were subject to expulsion. In 1897 an estimated 315,000 Jews lived outside the Pale, 21,000 in St. Petersburg, 14,000 in Kharkov, 10,500 in Smolensk, only 9,000 in Moscow, and 8,300 in Irkutsk on the shores of Lake Baikal in far off Asian Russia.

Within the Pale, urbanization of Jews was a striking phenomenon by the end of the century. Kiev counted 50,000 Jews by 1910 , up from 32,000 in 1897, and only 3,000 in 1863. Odessa counted the most Jews in a Russian city, with 17,000 in 1855 , , 139,000 in 1897 and 152,000 by 1904. In Polish cities Jews crowded into newly industrial areas such as Lodz which saw their Jewish populations rise from under 3,000 in 1856 to 99,000 in 1897. Warsaw was the largest Jewish city in all of Europe by the year 1908, with 277,000 Jews counted in the census figures.

Some scholars estimate that fully 8O% of Russian Jews lived in poverty, with over 20% receiving minimal forms of poor relief. In Zhitomir, closest to our ancestral home, one in every four Jews received free fuel from the Fuel Charities organized by the Jewish Community. The ability of the relatively comfortable Jews to support this burden was only possible due to substantial remittances from Jews in the wealthier industrial societies of the West, particularly Britain and Belgium.

Restrictions on freedom of movement and settlement were matched by economic constraints. Jews lost their role in the production and sale of alcohol, and their trade in salt and tobacco, all items which became state monopolies under the Tsars. Nor were Jews any longer permitted to maintain inns catering to the general public. Many of the former administrative functions of Polish days were taken away as well.

As old trades were lost Jews turned in desperation to other alternatives. Everywhere in the Ukraine the presence of Jewish peddlers was on the rise, men roaming the countryside from Sunday to Friday exchanging petty commodities for flax, linseed, rabbit and calf skin, poultry feathers and the like. In Poland, there emerged a new phenomenon, an urban Jewish proletariat, frequently linked to textiles, as Jewish artisans were driven into industrial production. Their employers were usually Jews as well, part of a small class of Jewish capitalists emerging in such industrializing towns as Lodz and Cracow. In Poland, railway builders like Herman Epstein attempted to rival the still more powerful Russian Jewish railway magnates such as Joseph (Evzel) Gunzburg and especially Samuel Poliakov. In the Ukraine there was far less industrialization and fewer Jewish success stories. One notable exception was the Brodski family, led by Israel and his sons Lazar and Leon, after their father's death in 1889. As their name implies, these Galician Jews were from Brody on the Austrian border with the Ukraine. They developed a large export business in Ukrainian sugar refined from locally grown beets, and singlehandedly transformed Russia from a net importer to a net exporter of sugar.

Despite the rare success story, pauperization became the general pattern of nineteenth century Jewish economic life. Russian authorities bore much responsibility for this misery. Tsar Nicholas I (1825-1855)set the tone; he despised Jews as heretics and Christ-killers and wished to convert Jews to Christianity and repress these who would not. His Minister of National Enlightenment, S.S. Uvarov, wished to modernize Jews along lines of their brethren in Western Europe in the hopes they might assimilate to Russian cultural and religious norms through reason. His ministry sponsored major reforms in two broad areas, education and military service, which were to have tremendous effects on Russian Jews since such changes marked the direct interference of the State in Jewish affairs for the first time.

Russian officials created state sponsored schools, staffed by modern, progressive Jews who were secular in outlook. While they educated a large number of Russian Jewish intellectuals, they aroused the unmitigated wrath of Jewish traditionalists, who saw modernity as yet another Christian plot; thus one by-product of State educational reform was the creation of deep rifts within the Jewish community. As a means of preparing Jews for modern life, this intervention might have been beneficial, however paternalist its method and suspect its motives. But subsequent Tsars and administrators let their rabid antisemitism intrude on policy. They soon began to resent the small but growing numbers of Jews entering into the liberal professions of medicine and especially law, and began a process of restriction of access of Jews to secular higher education. The technique they used was to apply quotas, the infamous numerus clausus, which limited the number of Jews permitted to attend secondary as well as higher schools to l0% within the Pale and 5% outside it. Similar restrictions were applied to the number of Jewish lawyers permitted to practice their profession.

The pressures and tensions such practices created in the shtetl were enormous. Our family was no exception. Grandfather Alter, a pious and traditional Jew, despised modernity as a Christian conspiracy and deplored the fact that his grandson Shame shaved his beard and read Russian books, skills and practices he had acquired by attending gymnasium, or high school, in Zhitomir. Young Leon remembers having to sit three times in order to pass an examination enabling him to begin secondary school in Zhitomir, since it was necessary to achieve a virtually perfect score to succeed. The ferocious competition of such a system produced frustrations and tensions among Jews, dividing them further. Meanwhile, in the gymnasium itself, this rigorous selection and compulsive attitude towards study made Russian Gentiles resent Jews even more, further contributing to endemic anti-Semitism.

Changes in military service regulations represented a second major intrusion into Jewish life. Nicholas I ordered Jews to be inducted into the armed forces by means of conscription, to be drafted in the same manner as Russian peasants. Earlier, Jews had been exempted on the grounds that they were physically and morally unsuitable for military service. The induction of an estimated 70,000 Jewish males over six decades caused untold hardships. Most either died or converted and few ever returned home. Resistance to service was as common among Russian Jews as it was for the general population, but not more so, despite anti-Semitic myths. Conditions of military service were harsh, and risks to life and limb great under the direction of callous and arrogant officers. Flight from military service was thus one of the first strong motives for emigration out of Russia. Notwithstanding the undemocratic nature of conscription in an oppressive State, Jews actually were over-represented in the Russian armed forces by the end of the century. In 1901, Jews constituted 5.73% of all service men in the Russian forces, yet their overall population was only 4.11%, thus exceeding their population ratio by nearly 40%.

If all this were not enough to make Jews think about emigration, the revival of terror through pogrom was a most dramatic incentive. Another round of severe pogroms occurred in the late nineteenth century, in the period from 1871 to 1906. The first of these violent outbreaks took place in Odessa, in 1871, where Jews were beaten, their shops and homes looted. What was new about this period was that some of the attacks were thought to have been officially instigated, especially those of 1881 which struck at Kiev, Odessa once more, and other larger centres south of Kiev. The nearest attack to Ostropol occurred at Zhitomir in 1905. Numerous attacks on the shtetls went unrecorded as the local peasants used anti-Jewish violence as an outlet for their economic discontent.

In the face of misery and hostility in Russia it is little wonder that the myth of the New World as a land of great opportunity had considerable appeal to Jews and to other minorities under Tsarist rule. Though the reality of conditions in the New World was sometimes harsh, there was also great opportunity, coupled with a high degree of religious and personal freedom. The United States was quite obviously the best known of these goldeneh medina or “golden lands”, but emigration to Canada, Australia, South Africa and Argentina also occurred in unprecedented numbers. The myth and reality of the pull of the New World is sufficiently understood in North America that little detail needs inclusion here. Perhaps the timing is not so familiar. In the 1880s the immigration of Eastern European Jews to North America had just begun. Of the roughly 1.2 million Jews who arrived in the U.S. between 1871 and l9l0, only 10% reached North America before 1891. Similarly, in Canada, there were only 2,443 Jews in the entire country in 1881, increasing to some 6,501 by 1891. By 1901 the number had increased to 16,401, and by 1911, to 74,564. These figures demonstrate clearly that when Moses Echenberg, son of Samson and Clara, left Ostropol for Canada in 1886, he was very much a pioneer in several senses of the term.

The route from the Ukraine to the New World varied but our ancestors in Ostropol were relatively well situated to benefit, however backward their shtetl was in other respects. Most migrating Jews went first to the Galician frontier city of Brody, inside the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which became the point of departure of a journey via Hamburg, Antwerp or Liverpool, to the New World. Brody was only a short distance west of Ostropol, on a route that family members such as Alter Echenberg used frequently in his egg exporting trade. While we do not know the precise circumstances which prompted him to depart, we must be eternally grateful to Moses, whose Centenary in Canada we are celebrating this year. He was the prime mover in what was to become an exodus of Jews from Ostropol. As soon as he could, he sponsored the arrival of his bride-to-be, Leah, and, soon after, of his younger brother Menassa. When Moses and Leah moved to Sherbrooke in 1893, their presence there became a point of settlement for kin and fellow Jews of Ostropol alike. Within a decade and a half, almost all of the relatives of Moses and his wife Leah had joined them in Sherbrooke. Other landsmen followed, the Gillicks, the Gilmans, the Greenbergs, and the Schmoklers, to name a few.

Ostropol today from Google earth

Sherbrooke Quebec in 1887 as it appeared at the time of migrations from Ostropol

The last emigration from Ostropol occurred in the years immediately following the First World War. A dramatic exodus took place in 1920, involving the departure of' the family of the late Moses Echenberg, son of Alter, accompanied by other Jewish families of Ostropol. Moses had died of a ruptured ulcer under stressful conditions of war, revolution and a typhoid epidemic in 1917. His eldest son, David, had emigrated to Sherbrooke nine years earlier, in 1911, sponsored no doubt by one of his cousins or uncles. Two sisters, Munya and Buzya, were already studying in Moscow by this time . Caught up in their studies, personal lives, and the events of the Revolution, they opted to remain in the Soviet Union. But by 1920 fears for the personal safety of the family prompted the Echenbergs in Sherbrooke to mount a veritable relief expedition to come to the aid of Jews in Ostropol. Through the prodigious but controversial efforts of Benjamin Richman, who had been dispatched to rescue the family, the group finally reached Warsaw, Antwerp, then Halifax and Sherbrooke, after numerous adventures and at considerable financial expense to the family sponsors in Sherbrooke. Included in this exodus were the following Echenbergs: Grandfather Alter; widow Hannah; eldest daughter Naomi Kitner, her husband Charles (also an Echenberg family member in his own right), their young sons Myer and Murray Kitner; and Leon and Reva, the two youngest children of Moses and Hannah. The entire group arrived in Sherbrooke in March, 1921. One year later the last emigration occurred, bringing the Blitt family as well as Isidore Echenberg, the youngest son of Sulig. In Sherbrooke he was reunited with his father as well as his brothers Louis, Sam and Jack, and with his sister Clara.

Although no one could imagine it then, the Echenberg departure from Ostropol would for the most part spare our family from the direct effects of the worst holocaust in Jewish history. All of Volynia and most of the Ukraine were occupied and ravaged by the Nazis during the Second World War. Those Jews who could not flee east to lands still held by the Soviet army would perish. Among these innocent civilian victims were our relatives, the Kesten family, who had chosen to resettle in Poland instead of migrating to the New World.

While Ostropol did not disappear after 1920, the last remnants of shtetl life were soon snuffed out, first by the enormous social changes brought about by the Bolshevik Revolution, but especially by the Nazi terror. Ostropol still appears on Soviet maps today, and while no family member has visited the town, it is generally accepted by those who have travelled in the rural Ukraine that little trace of shtetl life remains.

Two of our family became symbols in many ways of the dramatic changes that took place in revolutionary Russia. Sisters Munya and Buzya Echenberg were among the first women of any nationality to pursue higher education in the waning years of Tsarist rule. Both studied in Moscow, where Munya became a physician and Buzya a linotypist, after having studied civil engineering. The two sisters married; each had two daughters and raised their respective children as assimilated Soviet citizens. Buzya briefly visited the family in Sherbrooke in the late l920's, and although attempts were made to persuade her to emigrate, ties of family and ideology caused her to reject this course of action. No one in our family in North America has had any contact with our Soviet relatives in the last twenty years.

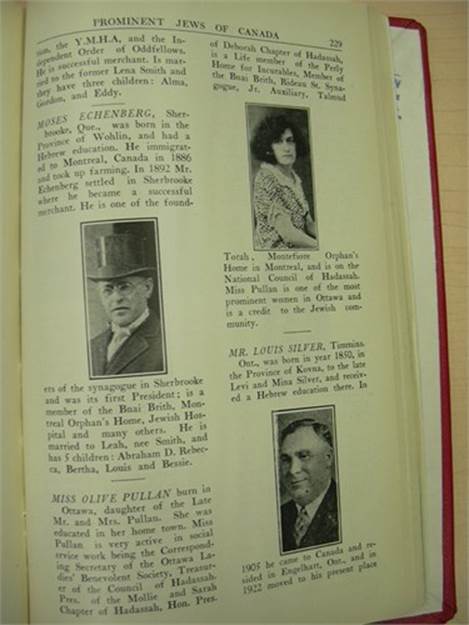

Moses Echenberg (b 1865) listed in Prominent Jews of Canada.

Louis Echenberg and his wife Basel Kushner in Ostropol 1890's

III. Early Years in Canada

Although the Echenbergs were in some ways typical of middle stratum shtetl Jews, their experience in North America differed from the vast majority of Jewish immigrants to North America in two fundamental respects. First, our pioneering ancestor Moses settled in Canada as opposed to the United States; secondly, he preferred a small town in the Eastern Townships to the largest city in Canada of the day, Montreal. Each of these decisions requires a historical context, although no precise evidence for Mose's choices has survived.

Jews were, to be sure, far fewer in number in Canada than the U.S. even if their numbers were growing in both countries. In 1901, Canadian Jews numbered some 16,131 in contrast to 1,777,000 in the U.S. By 1931, the spread was even greater, with 156,726 Jews in Canada as opposed to 4,228,029 in the United States. Notwithstanding the difference in magnitude, however, Jewish and non -Jewish immigration to Canada from Eastern Europe was increasing in the 1880's, so Mose's arrival in Canada, while unusual, was not unprecedented.

The Jewish Community in Canada formally began with the British Conquest in 1759. Under the French regime, Jews, Protestants and other non-Catholics had been prohibited from settling anywhere in the French colonies. When General Sir Jeffrey Amherst captured Montreal in 1760, one of his staff members was Lieutenant Aaron Hart, a British Jew, who, along with other British soldiers, decided to settle in Canada after it was formally annexed to Britain in 1763. Hart became the first English-speaker to take up residence in Trois Rivieres, where he amassed a huge fortune in real estate and especially in the fur trade. Hart raised his family there as Orthodox Jews, although one son, Moses, disappointed him by becoming a notorious libertine. The eldest son, Ezekiel, on the other hand, was responsible for a great breakthrough in Jewish rights in the British Empire, when, in 1832, he was finally allowed to swear his oath on the Old Testament, as opposed to the Christian Bible, and to take up his seat as an elected representative from Trois Rivieres to the Legislative Assembly in Quebec.

Apart from the Harts, only a handful of Jews settled in Canada until after Confederation in 1867. Among these were such early Montreal notables as Rabbi Abraham de Sola, who taught Hebrew and Oriental Literature at McGill University, and Lazarus Cohen, a wealthy entrepreneur and philanthropist who founded the Young Men's Hebrew Benevolent Society. Other early Jews were encouraged by immigration agents to settle in villages along the St.Lawrence, from Kingston, Maberly, and Lanark to Lancaster, where our own pioneer, Moses Echenberg, was to spend his first Canadian winter. Gradually Montreal became the focus of Jewish life in Quebec and Canada as a whole, in that period.

This Jewish Canadian community was in its infancy when Moses Echenberg arrived sometime in 1886. Unfortunately, only the barest facts about his emigration have survived. He was born on 5 September 1863, the second of three sons of Samson and Clara Echenberg; at the age of twenty-three he left Ostropol forever, and by an unknown route, reached Canada in 1886. Family traditions do shed some light on Moses's actions. One version, transmitted by Moses's daughter Bertha Levinson to her son Ed, has it that Moses intended to immigrate to Palestine, but that on reaching Odessa on the Black Sea, he was dissuaded from his original goal by a ticket-selling sharper, who, seeing that Moses could afford the more expensive fare to far-off Canada, sold Moses on this idea in order to obtain a larger commission.

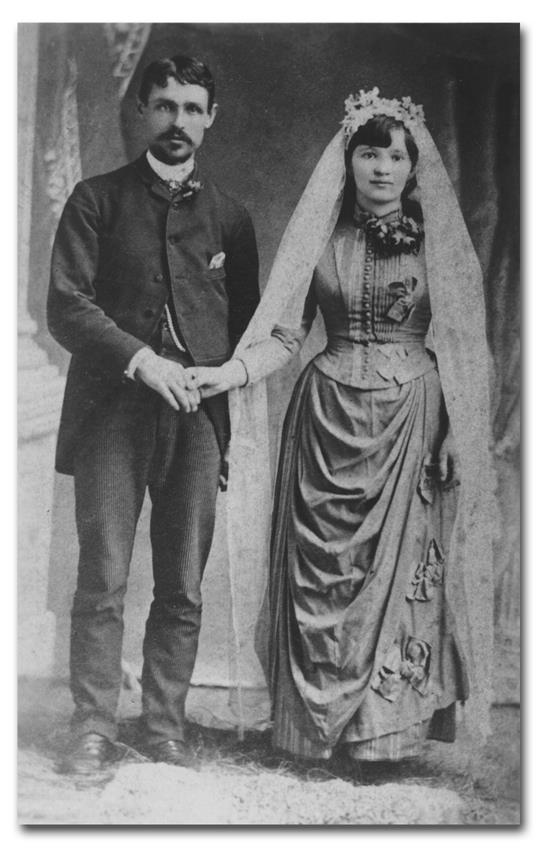

Moses Echenberg (b 1863)and his wife Leah Smith. He was the first Echenberg to emigrate from Ostropol to Sherbrooke.

A second tradition has come down to granddaughter Ruth Tannenbaum, who remembers Moses well for having lived in his home on 5 Prospect Street in Sherbrooke for several years. Moses, like other Jewish boys, had little access to Western education, and instead learned Yiddish and some Hebrew. But was secretly learned· Russian from a priest, and this opened up new intellectual horizons for him. Moses was neither a Talmudic scholar nor an intellectual with strong Jewish cultural ties to Yiddish literature. Instead, his favorite authors were English writers, especially Dickens, whom he read in Russian translation. This particular source of Western ideas made Moses an Anglophile his entire life. Perhaps his fondness for things British may have influenced him to elect British North America over the United States as a place to make a new life for himself

By themselves, these oral transmissions cannot stand alone, but they do offer several insights. Odessa was in fact the city on the Black Sea from which Moses's fiancée, Leah Spiegelbord (Smith), left Russia. Moses might have departed by this route as well, though an exit west through Brody was more likely, since it was closer and familiar to the Echenberg extended family. While it could have been possible, the immigration of an Eastern European Jew to Palestine as early as 1886 would have been exceptional. Alternatively, the idea of a ticket seller persuading him to choose Canada has the ring of authenticity since Canadian immigration authorities were paying premiums to agents to help attract settlers to the new lands of the Canadian Northwest.

As to personal motives for his departure, in addition to the general reasons for emigration from Russia already discussed, it is also possible that Moses was seeking personal opportunity not available to the younger sons especially in the deteriorating economic circumstances of the shtetl. As the second son, Moses had the freedom to act denied the eldest son, Israel (Sulig), but he probably also had mere limited economic prospects as well. Perhaps the father Samson would not have allowed his youngest, Menassa, to leave first, so Moses was the more likely first emigrant in this regard as well. It seems reasonable to deduce that Moses, with fewer ties than his brothers, and with the mere adventurous spirit that an inspired reading of the great nineteenth century novelists could satisfy, did not see himself as an egg collector in the Ukrainian countryside. Once decided upon migration, he opted not for the short distance migration to larger cities in the Ukrainian or Polish Pale, but for the marvelous lure of "America". It is then easy enough to visualize his willingness to be persuaded to go to Canada instead of the United States.

When Moses arrived in Canada sometime in 1886, there were strong forces pulling him to the west. On 16 November 1885, Louis Riel had been executed in Regina, formally ending the Metis rebellion and giving the young country of Canada full incentive to exploit the western grass lands through settler agriculture. Indeed, in 28 June 1886, the Pacific Express Number 1 steamed cut of Montreal towards the west coast, marking the first scheduled through passenger train across the enormous expanse of Canada. Given the publicity attached to this event, and Moses's penchant for adventure, it is a wonder the Echenbergs did not end up in Medicine Hat, Alberta, or Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.

Instead Moses was to choose an internal frontier, the Eastern Townships of Quebec, to build his home in the New World. Strictly speaking, by the 1880's, the "E.T.", as it is colloquially known, had ceased to be a frontier area. Under the French regime, seigneurial settlement had clung close to major rivers, the St. Lawrence of course, and the Richelieu, but not the St. Francis, save for a few communities at its mouth near Sorel. The Abenaki clan of the Iroquois nation certainly fished the region's rivers and lakes, and hunted its woods. Archaeological traces suggest that Sherbrooke, at the confluence of Magog and St Francis, may have been an important gathering place. The E.T. was also visited by a major invading force of British troops from the south when Rogers's Rangers attacked the French during the Seven Years' War in the middle of the eighteenth century. But the development of the E.T. as a region of white settlement came only after the American Revolution when the so-called United Empire Loyalists, as refugees from the south were called, were offered land for settlement in some eleven counties or townships between what was to become the border of New England and the St. Lawrence lowlands. Soon the Loyalists were joined by New England pioneers crossing over in search of more open country to farm. But major developments awaited the period from 1830 to 1850 when the British American Land Company was formed to sponsor a large influx of British settlers.

The mid-century marked the heyday of English-speaking dominance in the E.T. In 1861, Anglophones were not only the majority of the region, they formed the largest concentration of English-speakers in all of Quebec, their numbers then reaching close to 90,000, as compared to some 65,000 English-speakers in the Montreal area. Although this Anglophone population declined thereafter, it stabilized at roughly 75,000 until the end of the century. Between l901 and 1931, a further decline took place, but between 1931 and 1981 Anglophone Townshippers stabilized at roughly 55,000. While much of this population was rural, four urban centres did develop. Sherbrooke and Drummondville exploited the hydro-electric potential of the St. Francis to become textile manufacturing centres; Granby became a marketing town for dairy and garden farming, while Thetford grew as a small mining town sitting on a rich vein of asbestos. Also contributing to the wealth or the region was the pulp-and-paper industry. Cut logs were run down from Megantic and Lake St. Francis to mills up stream of Sherbrooke at East Angus, and downstream at Bromptonville and Windsor Mills. Between 1871 and 1891 Sherbrooke doubled its size to 8,500 people, still a small town with unpaved streets, perhaps, but already the largest town in the E.T., and a much more prosperous and modern place entirely than the Ostropol that Moses had so recently known.

Two themes emerge from this brief demographic sketch, the growing influx of French speakers and the out-migration of English speakers. At first, Anglophone demographic dominance was also reflected in economic and political power, although concentrated in a few hands. The figure of Alexander Galt, and his successor, Richard Heneker, stand out. Galt headed consortiums which controlled land, transportation, banking, and manufacturing; the British American Land Company, which controlled most of the land; the St.Lawrence and Atlantic {Grand Trunk) Railway, which, by cutting through the Townships to Portland, Maine, provided Montreal with its shortest link to an ocean port open all year round; the Eastern Townships Bank, founded in 1855; and the Sherbrooke Cotton Factory, which Galt financed in 1845. As Galt moved on to national politics he was succeeded as commissioner of the British American Land Company in 1855 by Heneker. By the 1870s Heneker had become, in addition, president of the Eastern Townships Bank and of the Paton Manufacturing Company, the woollen mill which was Sherbrooke's largest employer. At various times before he retired to Britain in 1902 Heneker was mayor of Sherbrooke, chancellor of Bishop's University , established in 1845. Bishop’'s College School had been created eight years earlier, in 1837), and founder and first president of the Sherbrooke Protestant Hospital.

Galt and Heneker were able to maintain political hegemony as well. Even after French speakers became a majority of the region, the Townships sent Anglophones to the legislature in Quebec City and the parliament in Ottawa. Heneker personally controlled Sherbrooke municipal government, and although he could not prevent the ascendancy of a French speaking mayor for the first time in the l880's, even though a French speaking majority had existed since the early 1870's, he made sure that city council preserved the right to choose the mayor until 1898, and that Anglophone sections of the city were over-represented on council until 1889.

The Eastern Townships suffered a relative economic decline in the late nineteenth century. One major cause was the growing concentration of power in the hands of Montreal and Toronto magnates. The Grand Trunk was bought out by the Canadian Pacific, based in Montreal, and Montreal businessmen took control of the Paton woollen mill. Most significantly, the Eastern Townships Bank gradually lost the ability to compete with the emerging Canadian giants. At one time, the E.T. Bank's vocation had been to serve regional interests by supporting E.T. farmers and small businesses. As many Townshippers began to move west in the 1870's and '80 s, their bank followed, at one time counting some 40 branches in the E.T. and in western Canada. But this expansion weakened the bank and by 1912, no longer able to compete, the Sherbrooke-based bank was bought out by the Toronto-based Canadian Bank of Commerce.

Though still a thriving region, the E.T.'s agricultural limitations had been reached, especially in comparison with the opening up of the cheaper and richer western prairie lands. Younger sons of English-speaking Townships farmers were lured west, their numbers replaced by French-speaking migrants who, in greater numbers , were finding jobs in the various Anglo-controlled industries of the region.

The Jewish community in the Townships may have had its beginnings with an advocate named Reuben Hart, possibly related to the Hart family of Trois Rivieres. He is listed as a resident of Sherbrooke by the first official Gazette in 1863. Also listed was one Jacob Hirsh, merchant in Richmond. By 1881 the official census counted some 20 Jews living in Sherbrooke, while the Sherbrooke City Directory of 1887-88 listed seven Jewish heads of families or individuals in a town of 8,500 persons. They included three shopkeepers on Wellington Street, L.Kellert, J.Levinson, and H.Samuel, and a tailor, J. Rosenvinge. Rather surprisingly, more Jews in that period lived in rural villages and farms than in town, as the following figures, taken from the 1891 Census, indicate:

County |

Jewish Residents in 1891 |

Sherbrooke |

26 |

Lennoxville |

1 |

Richmond-Wolfe |

8* |

Missisquoi |

8 |

Compton |

7 |

Stanstead |

5 |

Drummond |

2 |

TOTAL |

57 |

* It is entirely possible that this figure includes Moses and Leah Echenberg and their two young children, Abe and Becky.

In approximately 1891 Moses purchased a farm in the Danville area and settled in the Eastern Townships for the first time. Whether the four Echenbergs are included among the 57 Jews listed in the 1891 Census, or whether they arrived a year later, it is clear enough that they were a tiny minority in a region that then counted some 75,000 Anglophones and a slightly larger number of Francophones.

Moses's route to the Eastern Townships was indirect. After landing in Canada in 1886, he lived first in Lancaster, Ontario, a small town on the St.Lawrence River, between Cornwall and the Quebec border. That first winter he boarded with the Glickman family and supported himself by instructing their children. In the spring he left for Montreal, hoping to accumulate enough savings to send for his fiancée Leah. His first job was as a labourer on the Victoria Bridge. Soon after he entered into partnership in a cleaning and pressing business in Montreal with Mr. Colt, an immigrant from a shtetl town near Odessa. In 1888 the two partners could afford to send for their loved ones. Leah travelled from Ostropol to Odessa to join Mrs. Colt and her children, and together they sailed for Canada. Leah and Moses were married in the fall of 1888. Their first two children were born in Montreal, first Abe in 1889, and then Becky in 1891.

Soon after Rebecca's birth, Moses and Leah reached an important decision. They ended their partnership with Mr. Colt, and abandoned the big city to fulfil a dream dear to many shtetl Jews because it was denied them. Moses tried his hand at farming, making a down-payment on a farm near Danville, Quebec, some thirty miles from Sherbrooke. Whether because of the high risks of farming in Northern North America or through Mose's total inexperience, the experiment was a failure. Within a year or two the Moses Echenberg family had abandoned Danville, and in 1893, moved to Sherbrooke. Moses took up peddling in the neighbouring countryside while Leah helped make ends meet by selling second-hand furniture out of a shed behind their house in the East Ward. Three more children were born in those early days in Sherbrooke, Bertha in 1895, Sam in 1897 and Bessie in 1899.

Samson Echenberg (b. 1835) and his wife Kaila Freida Rosenbloom. He was the son of the original Moses Echenberg of Ostropol who chose the Echenberg patronymic. He emigrated to Sherbrooke with his 4 sons and 1 daughter.

Meanwhile, the Echenberg extended family in the New World was also growing. Moses sponsored the immigration of his youngest brother Menassa, then twenty-three years old, and he arrived in Sherbrooke on July 1894; perhaps by coincidence, perhaps because this was a crucial age for determining military status in Russia, both brothers were the same age when they left the shtetl forever. In 1895 Menassa opened a clothing store in St. Hyacinthe, which he maintained for four years before returning to Sherbrooke. Within two years of his arrival in Canada, Menassa married a Montreal girl, Rebecca Lehrer, and the couple had two children in St. Hyacinthe, Clara in 1897 and Henry in 1899. Within a month of the birth of their third child, Leah, in 1900, Rebecca died of complications resulting from childbirth. On 17 February 1902, Menassa remarried, this time to Eva Etta Holdengraber, daughter of Moses Holdengraber of Sucaeva, Austria. Clara stayed with her father and step-mother, Henry went to live with his maternal grandparents, the Lehrers, in Montreal, while Leah, the youngest, was put out to board with a French-Canadian family. While the Lehrers and Echenbergs may have shared a similar economic status, one family lived in the sophisticated world of Canada's largest city while the other shared the experiences of small town Canadians. Young Henry attended Westmount High School, and later, McGill University, graduating with a law degree.

Around 1900 Moses arrived at yet another of his dramatic decisions, this one dictated by his health. Doctors had diagnosed his chronic bronchial condition as tuberculosis and advised a drier climate, the only hope for arresting the then incurable disease. Moses and Leah sold their belongings, packed their five children, from eleven year old Abe to infant Bessie, and boarded a train for the American south-west, Arizona, perhaps. Instead of the desert, the harried family found themselves in the Rockies, in Denver, Colorado, where Moses worked for a time as a streetcar conductor. Eventually, the family wound up in Silver City, Colorado, where Moses may have tried his hand at prospecting. Family traditions remember this episode as a nightmare of poverty and misery in what was then a lawless frontier. Leah is said to have decided that they had better return to Sherbrooke, where Moses might die but at least the family would not starve.. M Menassa sent money and the bedraggled adventurers limped back to the comforting New World shtetl of Sherbrooke in roughly 1901 or 1902. As it happened, Moses lived on until his seventies, surviving Leah by several years.

By the turn of the twentieth century then, Sherbrooke was becoming something of a haven for Moses and the other Echenbergs. It represented a middle ground in the exciting but risky economic world of North America; it was neither a large metropolis such as New York or Montreal, with its handful of Jewish capitalists and its many more working class Jews hemmed into overcrowded tenements. Nor was it a wild mining frontier town such as Silver City, or a remote farming village as experienced by Jewish migrants to Saskatchewan for example. It resembled instead in some respects one of the larger shtetl towns of the Ukraine, a place to conduct small business and maintain solid family ties. It was, in short, a small lake but not a pond, a hedge against the larger opportunities and risks of life in the big city. As such it had considerable appeal to Moses, Menassa, and the other family members who followed them. In other respects, of course, life in Canada stood in marked contrast to the capricious conditions of Tsarist Russia. Our family was able to preserve the best features of the shtetl, and at the same time rid themselves of its many disadvantages. Jews in Sherbrooke became citizens of a democratic society, and were able to participate directly if cautiously in the affairs of the larger community, a process we shall examine next.

IV. Growth of the Sherbrooke Jewish Community.

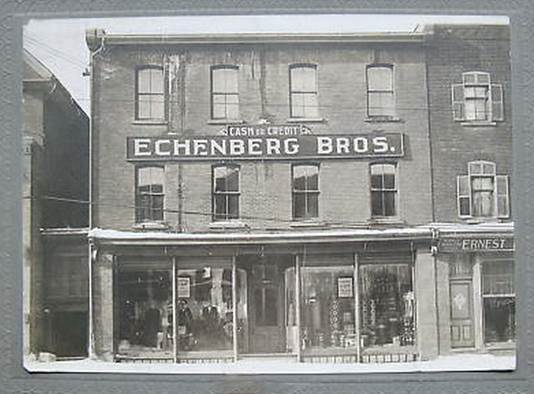

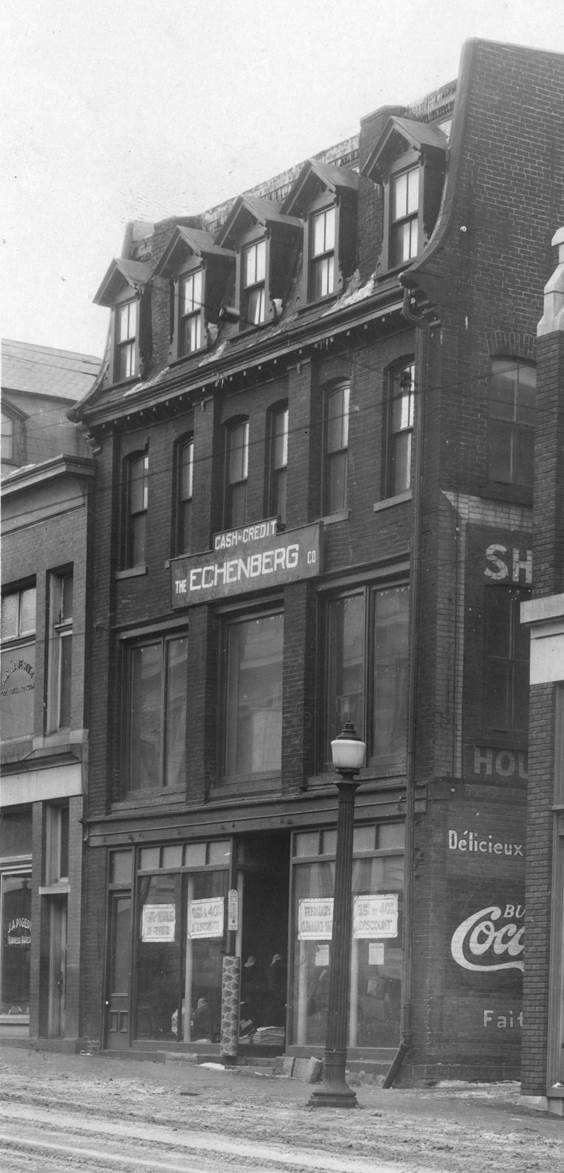

After he returned from his misadventure in the American Rockies, Moses Echenberg's economic fortunes finally began to improve. In 1902 he and Menassa formed the firm of Echenberg Brothers, furniture dealers, expanding perhaps on what Leah had begun years earlier. By 1910 the firm was sufficiently prosperous to allow the two brothers to purchase the valuable business block on Wellington Street that would become a commercial landmark to generations of Sherbrookers. Benefitting from the economic boom before and during the First World War, :Moses and Menassa, as well as some of their Echenberg cousins who had followed them to Sherbrooke, invested in commercial real estate, By the inter-war period, most had become comfortable and a few, wealthy. Some measure of Moses's new prosperity can be obtained from his family home. At 5 Prospect Street, in the middle class North Ward, Moses built a large, fashionable clapboard structure on a large property. While less grand than some of the imposing brick or stone edifices of the wealthiest Anglos in town, ·Moses's house would become a symbol of prosperity and especially of permanence to the people of Sherbrooke in general and to the Echenberg extended family in particular.

The Echenberg presence in Sherbrooke grew in numbers as well as in strength. Moses and Menassa's eldest brother, Israel, called Sulig, had chosen to remain in Ostropol. But as hardships mounted there, and news from Sherbrooke promised a better life, Sulig encouraged his sons to emigrate. In 1907 the oldest son, Louis, arrived in Sherbrooke, accompanied by his wife Basel and young son Sidney; next came the second brother, Sam, a year later with his wife Fanny Budning and their son Issie; and finally in 1910 came Sulig himself with two more children, Jack and Clara. The youngest son, Isidore, remained in Ostropol and was the last Echenberg to leave there, departing in 1922.

Echenbergs in Sherbrooke circa 1911

The steady emigration from Ostropol continued. In 1911 Dave Echenberg, oldest son of :Moses and Hannah and grandson of Alter, became the first member of the senior line of Echenbergs to cross the Atlantic, sponsored by his kinsmen in Sherbrooke. A few years he would marry a daughter of the junior line, his "half"-second cousin Rebecca. Their daughter Ruth, with Echenberg parentage on both sides, would take on the role of custodian of family tradition and prime mover behind the Centenary festivities we are celebrating this year. In 1912, Dave was followed by more Ostropol emigrants, Joseph Smith, Leah's father, and his children by a second marriage, Sam, Mindel, and Manasseh.

Not all members of the extended family chose Sherbrooke as their home. For a few, it was only a way-station in a migration journey that would bring them west to Chicago, Nebraska, and California, or south to Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Others went to these mainly U.S. destinations directly from Ostropol, as was the case for the Richmans who settled in the New York area, the Kitners, brothers of Charles, who went first to New York and then to Omaha, Nebraska, and the Blackers who established themselves in Philadelphia and Cleveland. The Blitt family, on the other hand, opted for nearby Montreal. Yet for all, even if symbolically, Sherbrooke was home. Bob Usher, who was born and raised in Montreal, remembers visits to the grandparents at 5 Prospect Street for High Holidays and other family occasions as being a chance to savour Baba Leah's knishes, the kind that· "melted in your mouth". Similarly, Ed Levinson, who also grew up in Montreal, provides the following impression of frequent visits to his grandparents' home.

"The vivid biblical scenes of the pictures on the walls, particularly that over the sewing machine, of the Solomonic judgement about to be made with the babe raised high in the soldier's hand and the sword about to cleave it in two. The Reverend Mittleman (the shohet, or ritual butcher of animals and poultry)downstairs in the white washed basement, blood splattering the walls as the headless chicken collapsed in its final resting place. A rather mysterious aura of foreigness enveloped people and the events and the things that were Sherbrooke. Yiddish, which I had never heard spoken before. "Strange foods" that we had never had in Montreal. The fact that children were included in the life of the family, not set at a separate table at meals, not shooed out of the room when certain topics were discussed, though of course, the switch to Yiddish and sometimes to French signalled the obvious. And finally Pinochle - a game of mystery."

Summer visits, on the other hand meant living in the rustic country around Katevale on Little Lake Magog, some 12 miles from Sherbrooke, where each branch of the Echenberg extended family built or purchased lakefront "dachas", their cottages in the country.

The first decade of the twentieth century also saw significant growth in the Jewish community of Sherbrooke. In 1906, Rabbi J.G.Laxer, who presented papers from the Jewish Theological College of the District of Chernuvich, Austria, was authorized by civil authorities to begin an official register of births, marriages and deaths. Retroactive entries back to the 1890's were made, our only written source for dates of these rites of passage of the early community. It is also worth noting that the Officers of the Congregation Agudath Achim in 1906 were identified as I. Smith, chairman, T.Vineberg, secretary-treasurer, and, as officers, H. Laxer, M. Echenberg, J.Echenberg, and Max Weinstein. No less than four of the six men were members of our extended family, indicating the degree to which the Echenbergs had come to dominate Jewish affairs in Sherbrooke. Precise identification of these four individuals is not as easy as it appears. I.Smith is probably Isaac, Leah's younger brother, while Max Weinstein was the husband of Sarah, the sister of Moses and Menassa. But it is not clear which of the two brothers was the M. Echenberg in question nor can we accept that the J. Echenberg listed was Jack. Family traditions indicate that he did not emigrate until 1910. Even if these are inaccurate, it seems unlikely that a new immigrant of the younger generation would be named an officer of the Jewish Community. One possible explanation is that the J is a misprint and that both Moses and Menassa were on the Executive.

The Echenberg dominance of offices in the Sherbrooke Jewish community was a measure of their strength in numbers as well as their growing economic clout. The table below (see the appendices for a fuller version) shows that the Jews of Sherbrooke had reached their numerical peak in 1921 and that out-migration in the 1920's had reduced their numbers sharply by 1931. In the early 1920's the Echenberg extended family probably included 75 persons, while approximately 75 mere Jewish residents of Sherbrooke were landsleit from Ostropol; thus fully 150 of the 265 Sherbrooke Jews could trace their origins to Ostropol:

Year |

Jewish Population |

Total Population |

Percentage of Jews |

1871 |

0 |

4,432 |

|

1881 |

20 |

7,227 |

0.28% |

1891 |

26 |

8,500 |

0.31% |

1901 |

66 |

11,786 |

0.5 1. |

1911 |

188 |

16,348 |

1.15% |

1921 |

265 |

23,660 |

1.12% |

1931 |

152 |

28,933 |

.52% |

Jewish population in Sherbrooke

As the Jewish population of Sherbrooke grew, changes in the structure of the community kept pace. A new Rabbi, the Reverend A. Wexler, is mentioned in the Congregational Register; he served from 1914 to 1919, when the Reverend A. Mittleman arrived. To this point the Congregation had rented premises for the High Holidays on Dufferin Street. But in 1920 a handsome synagogue was erected, an important symbol of the Community's prosperity and sense of belonging. The synagogue's Grecian-style white pillars and modern interior must have contrasted vividly with the primitive shtetl shuls older family members remembered. So too did the ritual. While nominally Orthodox, community life was distinctly modern and North American. Secular Jewish institutions dominated synagogue life: B'nai Brith, Hadassah, Ladies' Aid. A part-time cheder was begun for boys, and more rarely for girls, but attendance after regular school and on Sunday mornings, together with the powerful attraction of an assimilationist Anglophone Canadian culture, meant that Sherbrooke youths grew up with much stronger cultural than religious ties to Judaism.

During the inter-war period the family names Echenberg and Smith continued to figure prominently as synagogue officers, with Menasseh Smith in particular being the long-term president of the Congregation. Whatever his official title, Moses Echenberg was clearly the head of the Echenberg clan, and was so recognized by the civil authorities who named him a Justice of the Peace. This position suggested social as well as legal standing, and indicated the probity with which he was regarded. The house on Prospect Street became a meeting place for community members, and Moses was often called upon to mediate business and other community differences. Moses also became involved in politics. He was listed in a publication entitled "Men of Today in the Eastern Townships", published in the inter-war period, as being a member of the Liberal Party.

Politics in Sherbrooke reflected a compromise worked out between the economically powerful Anglo minority and the numerically strong French-speaking majority. An unwritten agreement specified that the mayoralty of Sherbrooke should alternate between the two linguistic groups, a tradition that was maintained until the 1960's. Whatever competition there was for office took place in an informal primary within each language group; once a candidate emerged, he was normally acclaimed. On one occasion, Moses's eldest son Abe was approached by leaders of the Anglo community to become mayor, but he declined the invitation. Moses was an important fund raiser for the Liberal Party and daughter Becky was a Liberal scrutineer each provincial or federal election. More important than party affiliation were the strong personal ties the Echenbergs maintained with the two Liberals who dominated Sherbrooke politics in the first half of the twentieth century, Charlie Howard at the federal level as a Liberal M.P. and later a Senator, and Jacob Nicol, owner of La Tribune, the well-known Sherbrooke French language daily newspaper, who was also appointed to the Senate.

One informative example of how the Echenbergs exercised leadership in matters affecting Jews in Sherbrooke emerges from the correspondence of Moses's brother, Menassa, with the Canadian Jewish Congress in 1937 (see appendices).The period was one of rising Fascism and its concomitant anti-Semitism all over the world. In Quebec, an extremist wing of French-Canadian nationalism under Adrien Arcand preached its anti-Semitism openly, and hate literature was a constant problem. Menassa's correspondence reveals the preferences of Sherbrooke's Jews, which were consistent with the tendencies of Canadian Jews in general; to keep a low profile and work behind the scenes to appeal to the fair play of non-Jewish business and political associates. In this instance, Menassa was able to report that two officers of the B'nai Brith, Sidney Echenberg and Sol Niloff, had paid a friendly visit to the two major newsdealers in Sherbrooke, who had agreed not to sell the offending hate literature in the interests of good community relations.

By the inter-war period, the new generation of Echenbergs, born in Canada, had come to reflect attitudes typical of small town, middle class Anglo-Canadians. Once again, the family of Moses Echenberg set the tone. Moses communicated two strong beliefs to his children, an especially strong Anglophilia, and the then unusual view that daughters were entitled to as much higher education as sons, a position to which neither Orthodox Jews nor Victorian or Edwardian Englishmen subscribed.

His wife Leah shared his patriotism and took an active part in community affairs both among Jews and in the wider community. She was, for example, a prominent member of the I.O.D.E., the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire, of which her daughter Becky was to serve for a time as president. In other respects, Leah was a traditional Jewish mother, speaking Yiddish in the home, and cooking prodigious quantities of old country specialties, few of which would be endorsed today by Weight-watchers. Leah's hospitality was also extended to strangers, in the tradition of the old country balabatim. The late father of Dr. Harry Rosen, for example, gratefully remembered how, as a new arrival in Canada and Sherbrooke, he and others without families of their own were welcome on Sabbath at the Echenberg family table. Leah was also remembered by the French-speaking Roman Catholic community for her lovingness and generosity. When she died in 1936, three nuns paid their respect by praying beside her coffin at 5 Prospect Street, an ecumenical gesture impossible to imagine in Ostropol or even Montreal.

The children of Leah and Moses were model of Anglo-Canadian virtue, the girls outshining the boys in many respects. Bertha was among the very first Jewish girls to graduate from Macdonald College with a Teaching Diploma. She had a difficult time forcing her way into a teaching job with the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal (the PSBGM), but those who knew Bertha will testify that she was not the type to take no · for an answer. She not only taught school at Edward VII Elementary, near Van Horne Avenue, where among her many students was the gifted Canadian poet, A.M.Klein; she also constantly nipped at the heels of PSBGM officials. As her son Ed Levinson puts it, " Mother was a moralist and inclined to be piously aggressive when she believed that God was on her right hand." She railed against the school officials over their refusal to excuse the absence of her Jewish students for the High Holidays. Then, after she had helped in the struggle of Jews for this reform, she aggressively pursued non-observant parents, insisting they that they keep their children home on the Yom Tovim so as not to prejudice the hard-won right of observant families. Sister Becky not only followed Bertha's trailblazing path to Macdonald, she also boldly volunteered for overseas duty during the First World War. She joined the St. John's Ambulance Corps in Sherbrooke, and after being trained u a nursing assistant, was sent to England, the only Jewish member of her volunteer brigade. The youngest daughter, Bessie was a brilliant student, winning the Narcisaa Farand Scholarship to Bishop's University, which she attended during and after the War.

The boys on the other hand made their mark in commerce and the military.

Abe briefly attended McGill but then returned to Sherbrooke, suffering from a thyroid condition which later also precipitated Becky's early return from overseas' service in 1917, Abe apprenticed himself to his father and uncle in the furniture business, which he mastered sufficiently to become the epitome of the successful small town businessman, serving his stint as President of the Rotary Club, but turning down an invitation at one time to accept the Anglo nomination as mayor of Sherbrooke, Abe's younger brother Sam also left McGill after a year, in his case to volunteer for overseas duty as an enlisted man, He served in France and by war' a end in 1918 had been promoted to sergeant. On his return to Sherbrooke, Sam devoted far more energy to his military vocation in the militia (reserves) than he did to his job as salesman in the furniture store. His rise in the reserves was remarkable, to captain, major, and finally, colonel and commander of the Sherbrooke Regiment. By this time, the late 1930's, as another World War loomed, military service took on more seriousness. Many of the Jewish men of Sherbrooke served under Sam in the Regiment, and, after 1939 saw active duty. Echenberg veterans included Sam, Issie, and Harry, while sons of the Gilman, Linds, Vineberg, and other Jewish families of Sherbrooke served in various branches of the Canadian Armed Forces. Sam Echenberg served in various senior capacities in the Montreal area, Commandant of an internment camp on St. Helen's Island, then commanding Officer of the huge manning depot at Longueuil, finally retiring at the end of the war with the rank of acting Brigadier-General.

For this most Anglophile of Echenberg families, what might be called "their finest hour" occurred in 1939, during the visit of the newly crowned King George VI and Queen Elisabeth to Canada. As C.O. of the local regiment Sam was presented to the royal couple when they visited briefly in Sherbrooke. Then a bachelor, he chose sister Becky to accompany him. The event was captured by a photograph, of course, which then was prominently mounted on the wall at 5 Prospect Street. Becky's husband Dave, and their daughter Ruth, both astute enough to see humour in this Anglo-Canadian pomp and circumstance, labeled the photo "The Moment", and that term brilliantly captures the stuffiness and occasional snobbery of some of the more assimilated Echenbergs,

Col Sam Echenberg and his sister Becky greeting King George Vl and

Queen Mary in Sherbrooke, 1938

By education and culture, the Sherbrooke Jewish community was Anglophone. Two strong forces dictated this choice. First, since education was under the jurisdiction of the provinces, Quebec chose to maintain a dual system; a majority system, overwhelmingly French and Catholic, and a second system for Protestant and others. As Jews were uncomfortably thrust into the Protestant school system, many began to campaign for a separate Jewish parochial status by the turn of the century. In Montreal, this question would provoke deep rifts between "uptown" and "downtown" Jews, but in Sherbrooke the community was too small to think of separate schools, even if this had been attractive to them. Secondly, economic and political power in Sherbrooke resided clearly with Anglophones. Under the circumstances then, it is no surprise that Sherbrooke's Jews attended English-speaking Protestant Schools. The first cohort of children went to the East Ward Primary School, but because many lived among French-speakers, the children learned colloquial French from an early age. With affluence came a move to the North and a more homogeneous English-speaking environment. To learn French now required a strong commitment and pressure from parents as French instruction in the Protestant Schools was perfunctory at best. The prevailing WASP attitude of the day was to disdain French and some Jewish children absorbed this bias. But many Jewish parents did business increasingly among French-Canadians and urged the learning of a second language on utilitarian grounds.

The inter-war years and especially the world depression saw major economic changes in the community. Family quarrels and fallings-out over business matters adversely affected relationships as some Echenberg and other Jewish businesses failed. The community's limited resources were reserved for widows and orphans; others were expected to look out for themselves, moving away if necessary. Population figures indicate that the general limits of opportunities coupled with the depression saw the community shrink in size. Businesses struggled, with retail stores now offering credit selling in the manner of the early peddlers a generation ago.